Late Antique and Early Medieval Hispania by Pilar Diarte-Blasco

Author:Pilar Diarte-Blasco

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / Hispanic American Studies

ISBN: 9781785709975

Publisher: Oxbow Books

Published: 2018-08-08T16:00:00+00:00

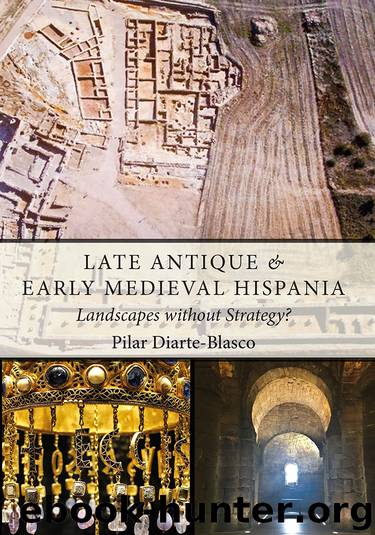

In fact, the magnificent complex of Pla de Nadal (Fig. 14) is not related to any simple landowner but rather, as noted above, with Thedomir, a notable Visigothic nobleman high in royal court circles, who had a significant role in events in the south-east of the Iberian Peninsula. The building, which had clear symbolic and representative significance, comprised a functional and rather austere ground floor, and a top floor, totally collapsed, from which came a huge number of architectural pieces – almost 800 fragments – including reused Roman capitals and also newer ones in an Eastern/ Byzantine style – signifying its use for both residential and ‘ceremonial’ representative functions (Ribera i Lacomba 2005b).

The identification is based, first, on a cruciform anagram that seems to correspond to a proper name starting with the Germanic root Teud- and, secondly, on a graffiti with the name Teudinir incised inside a scallop shell. However, the location close to Valencia counters such an attribution for some scholars (e.g. Gutiérrez Lloret 2013, 255). If, as seems likely, the heart/focus of the Kūra of Tudmīr was, in name and territory, a transcript of the dominion of the Thedomir, so it is difficult to accept that his residence lay outside of his own territory, and in the immediate vicinity of an urban centre that would become capital of the neighbouring and bordering Kūra of Valencia. However, we should recognise that pinpointing the borders between both territories is problematic, and so the exact identification of the building remains an open question. Pla de Nadal, nonetheless, remains the sole known example of a Visigothic rural palatine complex.13

Otherwise, we know of residences, mainly ones far from concepts like ‘representation’, and instead related more to peasants and, maybe, modest local elites. In recent years, the material visibility of the peasantry is starting to reveal something of their social structure and of the main traits in their relationship to landowners (Wickham 2005, 519–588). Useful sources to help clarify this relationship could be the so-called ‘Visigothic inscribed slates’ – labelled as Pizarras Visigodas (Velázquez Soriano 1989; 2000) – some of these found in archaeological contexts and others as casual finds, and encountered in the regions of Salamanca and Avila, a small area of the central Iberia, and dated between the 6th to 8th centuries. These slates are lists in Latin of census payments and some lists with names of peasants/farmers, as well as what can be labelled ‘schoolwork’, liturgical texts, psalms, letters and even a variety of legal documents. However, there are still problems of interpretation of these thin slates, which largely appear to represent a form of private, perhaps ‘estate’ documentation. There are three basic typologies to these slates: numeric, textual (with religious, contract sales or judicial texts) and figured (featuring drawings of religious buildings and agriculture works). One recent view sees a tributary significance to these slates, reflecting thereby some legal communications channel linking a central or regional authority with local powers/elites. Certainly, they are striking evidence for a literate and functional

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5102)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4798)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4749)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4344)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4193)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4090)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3989)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3972)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3424)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3350)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3326)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(3194)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3186)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(3146)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3116)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(3071)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2919)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2914)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2851)